Stack Machines: Shunting-yard

fundamentals « rpn-calculator « shunting-yard « io « jumps « conditionals « comments « calls « variables « stack-frames « heap « compilers

The RPN calculator (see previous post) was quite easy to implement, but in order to use it, everything must be written backwards. Re-gaining infix notation would be sweet.

Luckily, it looks like Dijkstra might have us covered with his shunting-yard algorithm.

Precedence

Infix notation requires rules that define the precedence of operators. Going back to the example of the previous post, the expression:

Is to be interpreted as:

Because the * operator has precedence over the + operator. It binds more

strongly, the operator with the highest precedence groups its operands,

enclosing them in invisible parentheses.

Associativity

Another consideration is associativity1. Generally speaking, associativity defines the grouping of sub-expressions within the same level of precedence.

An example would be:

Because + is associative, it can associate to the left and the right without

changing the meaning or result.

Associating to the left:

Associating to the right:

Both produce the same result: 6.

However, if we try the same with -, which is non-associative, it will not

produce consistent results.

If we take the expression:

Associating to the left:

Associating to the right:

Left associativity produces 0, right associativity produces 2.

Conclusion: The correct associativity in this case is left, and the

result we would expect is 0.

Parentheses

In addition to the implicit grouping between terms and expressions there can also be explicit grouping through parentheses, that supersedes the two previous forms of grouping.

These must also be taken into account when interpreting an expression.

Compilers

Enough math already. Let’s talk about compilers.

A compiler takes a high-level language and translates it into some sort of low-level machine code. Mathematical expressions are a subset of many high-level programming languages.

In 1960, the dutch computer scientist Edsger Dijkstra was working on a compiler for ALGOL60. Back then he referred to it as a “translator”. When faced with the challenge of precedence, he came up with an algorithm for resolving the precedence of these expressions.

This algorithm is known as the shunting-yard algorithm.

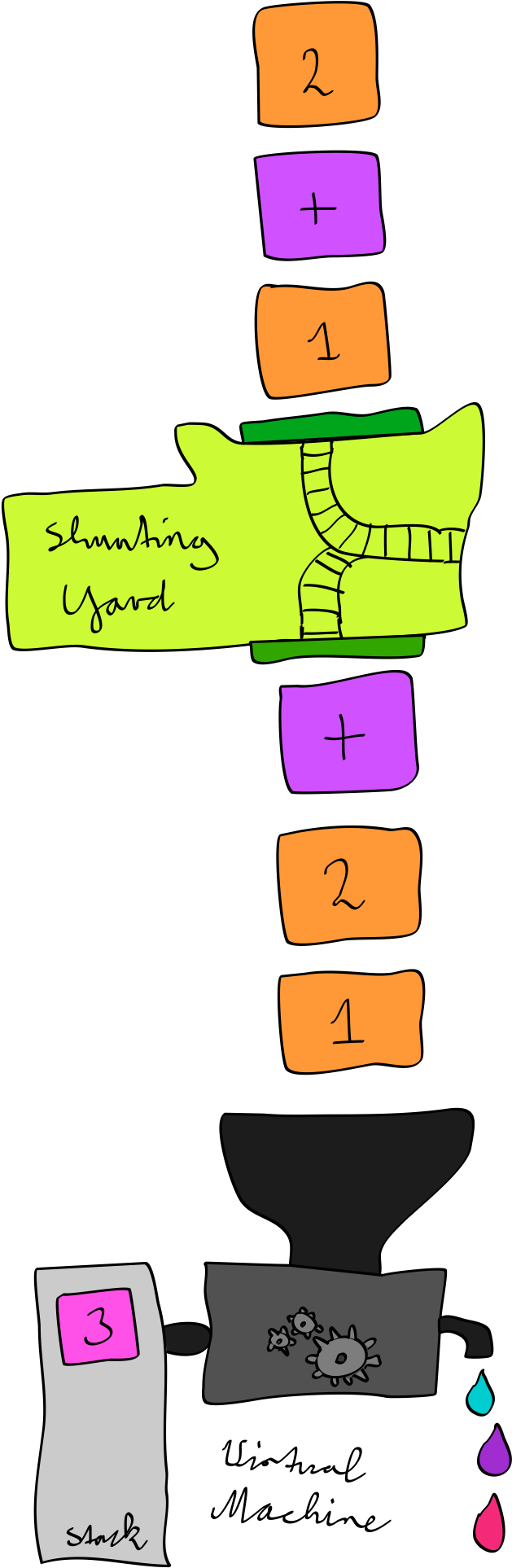

What it does is translate an expression from infix notation to something that is easier to understand for a machine: Reverse-polish notation, or postfix notation.

What this means is that we can take an expression as an input, then use shunting-yard to compile that expression into RPN, and finally use the existing RPN calculator to run it!

Shunting yard

The translation process shows much resemblance to shunting at a three way railroad junction in the following form.

I will not describe the shunting-yard algorithm in detail here. I will however try to give a high-level description of what it does.

The process starts with a set of input tokens, an empty stack for temporarily stashing tokens and an output queue for placing the output.

Based on pre-configured precedence and associativity rules, the tokens are shunted from infix to postfix in a very memory efficient way.

Read the Wikipedia page or the original paper for a more thorough explanation.

Implementation

Without further ado, here is an implementation of shunting-yard:

function shunting_yard(array $tokens, array $operators)

{

$stack = new \SplStack();

$output = new \SplQueue();

foreach ($tokens as $token) {

if (is_numeric($token)) {

$output->enqueue($token);

} elseif (isset($operators[$token])) {

$o1 = $token;

while (

has_operator($stack, $operators)

&& ($o2 = $stack->top())

&& has_lower_precedence($o1, $o2, $operators)

) {

$output->enqueue($stack->pop());

}

$stack->push($o1);

} elseif ('(' === $token) {

$stack->push($token);

} elseif (')' === $token) {

while (count($stack) > 0 && '(' !== $stack->top()) {

$output->enqueue($stack->pop());

}

if (count($stack) === 0) {

throw new \InvalidArgumentException(sprintf('Mismatched parenthesis in input: %s', json_encode($tokens)));

}

// pop off '('

$stack->pop();

} else {

throw new \InvalidArgumentException(sprintf('Invalid token: %s', $token));

}

}

while (has_operator($stack, $operators)) {

$output->enqueue($stack->pop());

}

if (count($stack) > 0) {

throw new \InvalidArgumentException(sprintf('Mismatched parenthesis or misplaced number in input: %s', json_encode($tokens)));

}

return iterator_to_array($output);

}

function has_operator(\SplStack $stack, array $operators)

{

return count($stack) > 0 && ($top = $stack->top()) && isset($operators[$top]);

}

function has_lower_precedence($o1, $o2, array $operators)

{

$op1 = $operators[$o1];

$op2 = $operators[$o2];

return ('left' === $op1['associativity']

&& $op1['precedence'] === $op2['precedence'])

|| $op1['precedence'] < $op2['precedence'];

}

In this case, $operators is a mapping of operator symbols to some metadata

describing their precedence and associativity. A higher precedence number

means higher priority.

An example of such a mapping:

$operators = [

'+' => ['precedence' => 0, 'associativity' => 'left'],

'-' => ['precedence' => 0, 'associativity' => 'left'],

'*' => ['precedence' => 1, 'associativity' => 'left'],

'/' => ['precedence' => 1, 'associativity' => 'left'],

'%' => ['precedence' => 1, 'associativity' => 'left'],

];

While all of those associate to the left, there are operations that commonly

associate to the right, such as exponentiation. 2 ^ 3 ^ 4 should be

interpreted as (2 ^ (3 ^ 4))2.

Another common right-associative operator in programming languages is the

conditional ternary operator ?:3.

Compiling to RPN

Time for an actual test run of this shunting yard infix to postfix compiler!

$tokens = explode(' ', '1 + 2 * 3');

$rpn = shunting_yard($tokens, $operators);

var_dump($rpn);

It produces the sequence: 1 2 3 * +. This looks correct, it should evaluate

to 7.

But let’s feed it to the existing calculator and see what happens.

$tokens = explode(' ', '1 + 2 * 3');

$rpn = shunting_yard($tokens, $operators);

var_dump(execute($rpn));

It agrees!

Now we have a fully-functional infix calculator that is the composition of an infix-to-postfix compiler and a postfix calculator!

You will find that it supports not only the operators +, -, *, / and

%, but also parentheses that are completely removed from the resulting RPN.

In addition to that, adding support for new operators is as easy as adding an

entry to $operators and an implementation to the switch statement in

execute.

Summary

- Shunting-yard translates infix to postfix.

- Implementation is quite straight-forward.

- Hey, look! It’s a little compiler!

-

Not to be confused with commutativity which defines whether the order of operands matters. ↩

-

I used the

^symbol for exponentiation, in many languages something like**is used instead. ↩ -

Too bad PHP messed that one up. ↩

fundamentals « rpn-calculator « shunting-yard « io « jumps « conditionals « comments « calls « variables « stack-frames « heap « compilers